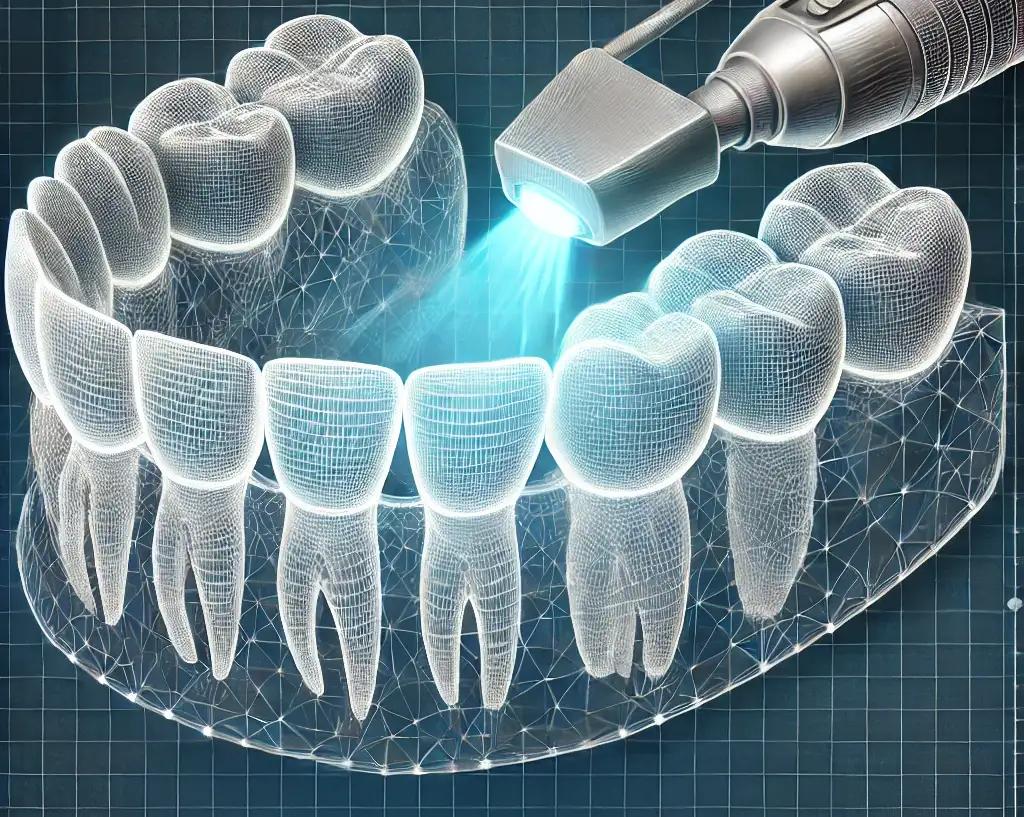

How Technology is Transforming Dentistry

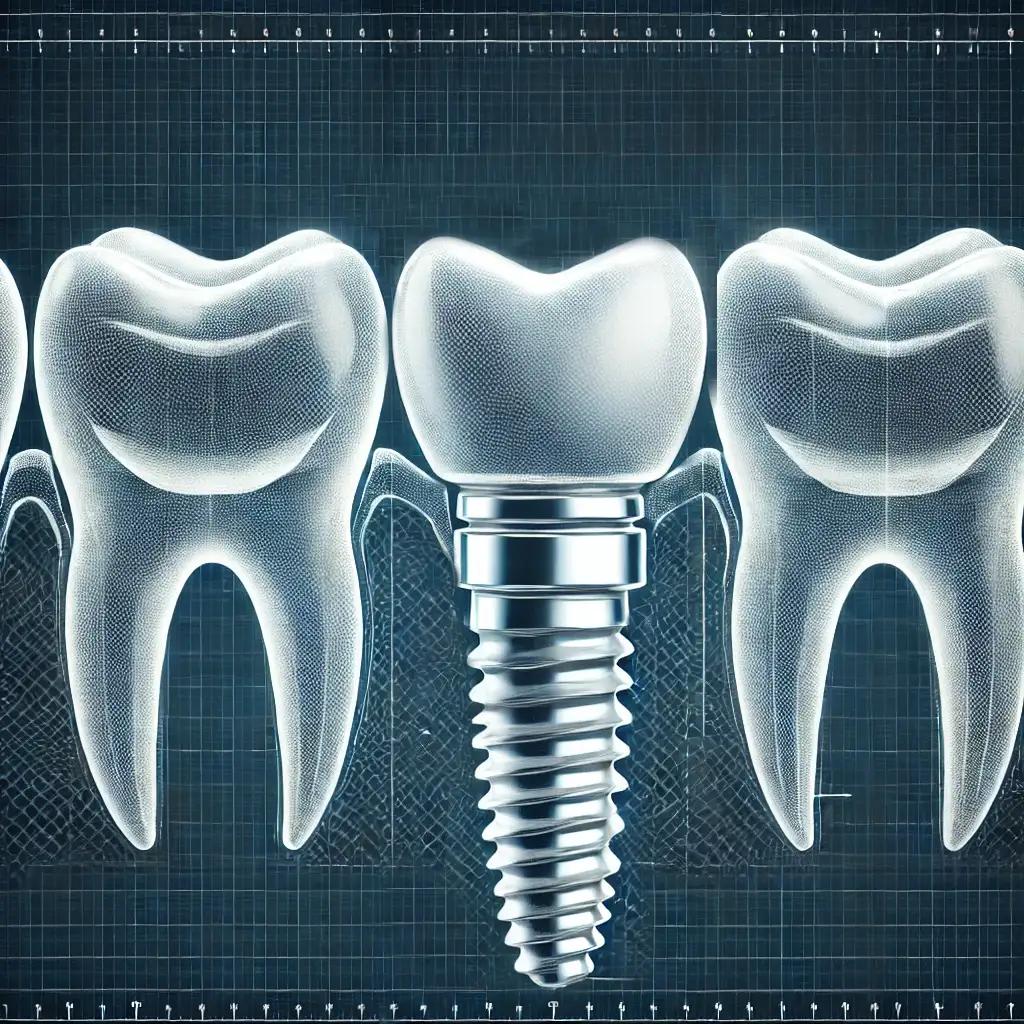

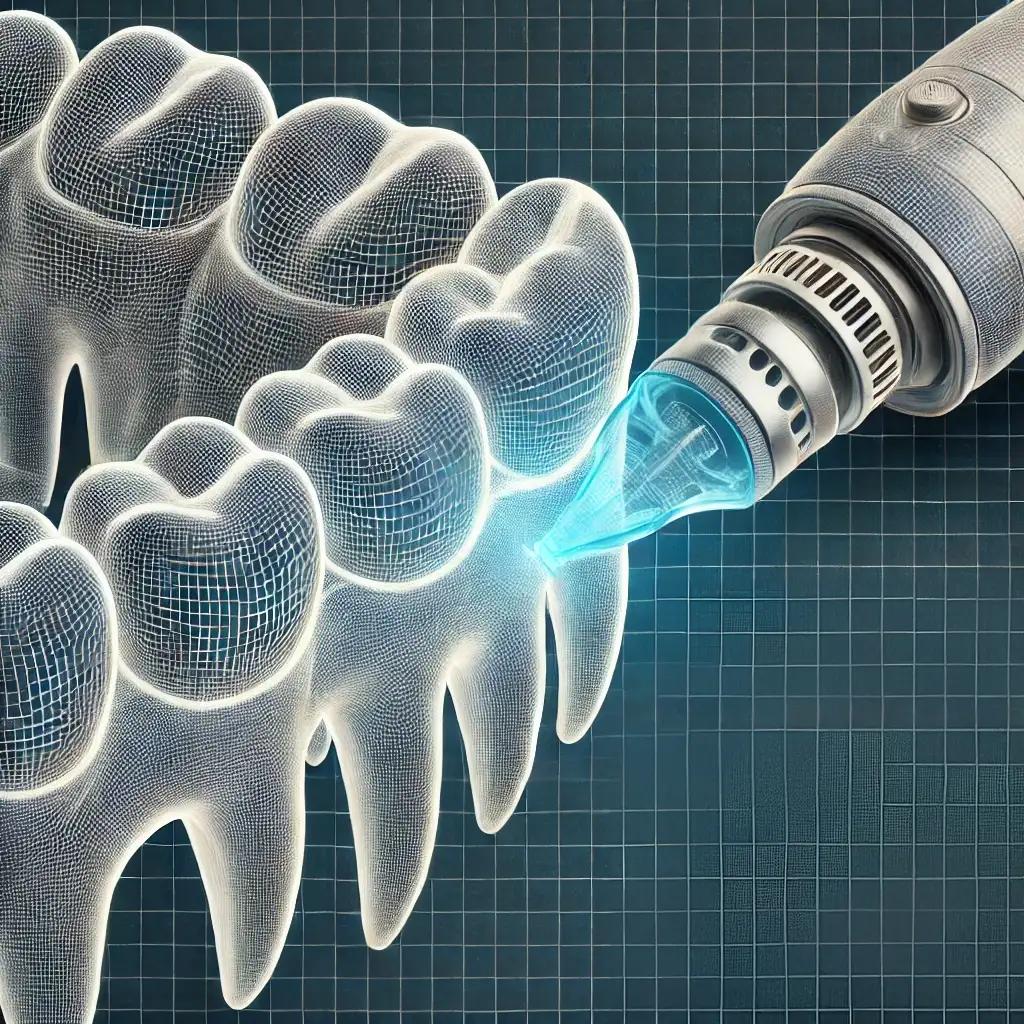

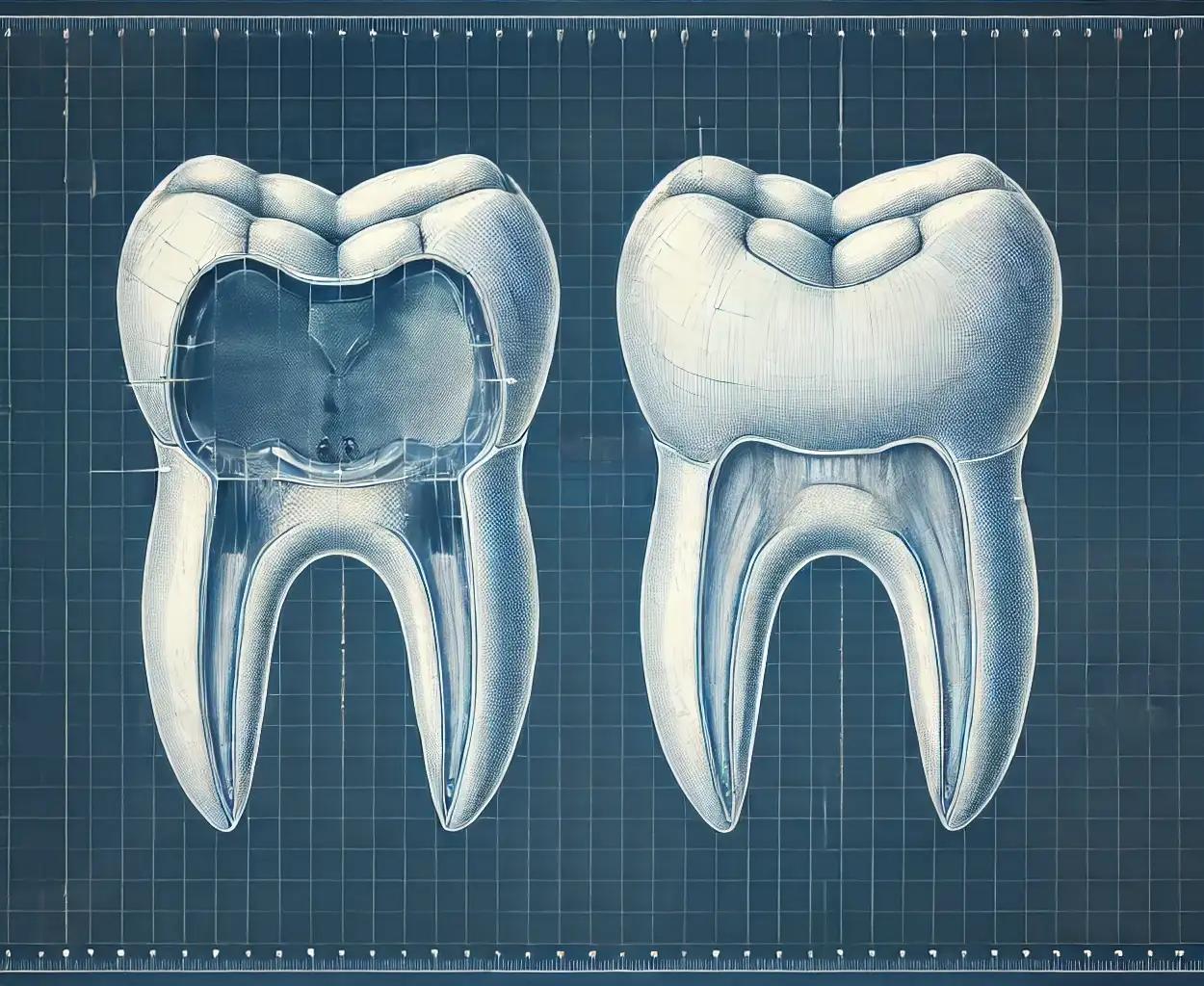

At McGann Family Dentistry in Lake Elmo, MN, we use advanced technology like 3D imaging and CAD/CAM to create natural-looking, durable dental restorations. Our innovative techniques ensure your smile is seamless, functional, and beautiful.